Agricultural commodity prices have covered a lot of ground in the past year. Soybeans, for example, began the year at $13 before rising to $16 in May and ultimately coming back to $13 today. While a growing basis has provided additional support for North Carolina cash prices over the course of the year, falling prices in Chicago beg the question: Was 2021 a flash in the pan or the start of something bigger?

Those working in agriculture understand well the cyclical nature of commodities, seeing periods of over-investment and expansion followed by low prices, disinvestment, lower supply and ultimately higher prices causing the cycle to repeat itself. Typically, we think of these cycles playing out over an easily observable time frame – 2 to 3 years – but, taking a step back, one observes larger patterns, dubbed commodity supercycles, that may play out over the course of an entire career.

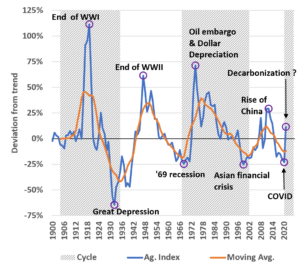

Historically, commodity supercycles were tied to periods of sustained growth in demand for raw materials, often coinciding with wars, and ultimately bookended by an economic depression or recession The diagram below illustrates how this played out for World Wars I and II but going back further we would see similar patterns emerge during the Napoleonic Wars of the early 19th century as well as during the US Civil War.

Beginning in the 1970s a new type of commodity supercycle emerged, this time rooted in monetary policy when the US suspended dollar convertibility to gold. Rapid inflation ensued and, aggravated by the Arab Oil Embargo, commodities began a long period of high prices, staying well above trend until the late 1980s.

The commodity price cycle freshest in the collective consciousness is the one attributed to the “Rise of China”. Due to a number of factors, China emerged from the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s on better footing than many neighboring countries and for the next 15 years averaged annual GDP growth of more than 10%, the highest, by far, of all the world’s major economies. For the purposes of agricultural commodities, this GDP growth translated into a westernization of the Chinese diet, leading to an unprecedented growth in demand for fats and proteins from the world’s most populous country.

It would appear that the trade war and COVID brought this most recent commodity cycle to a close but a key question confronting agricultural stakeholders today is whether the high prices enjoyed in 2021 are simply an aberration or the start of a new upward trajectory and a new cycle. Just as previous supercycles have been assigned a root cause, observers who contend we are in the midst of a new cycle are attributing it to the global push towards decarbonization. Decarbonization has the potential to lift agricultural commodity prices in many ways. Commitments against deforestation and environmentally minded biofuel mandates, for example, serve to limit supply and increase demand, thereby lifting prices. Decarbonization will also affect agriculture indirectly, first by increasing the cost of fossil fuels and, by extension, inputs like fertilizer, having the potential to crimp output and lift prices even further. Other factors, like a devalued dollar, could also lend support to a new commodity supercycle although prospects for even worse inflation in Brazil, muddy this aspect considerably.

While macroeconomic issues like commodity supercycles may seem abstract, and are well beyond anything that can be controlled on the farm, they do provide a valuable framework through which stakeholders in the agricultural value chain – growers included – can make investment decisions. The trick with any cycle, whether it’s 3 years or 30, is to be on the right side of it.