The name of the game among producers in commodity markets is to support prices by winding down stocks. In this blog post we begin by exploring this relationship and then illustrate the lengths that producers, should, in theory, go to achieve tight stocks. In short, the relationship between ending stocks and price is often so sensitive in commodity markets that it may actually pay to destroy or export at a loss, some small share of production, in order to make money on the remainder. While this type of behavior would be ill-advised and nearly impossible to coordinate in the soybean sector we will highlight a few markets where these practices have been carried out – even if they fall under the category of anti-competitive behavior or in violation of World Trade Organization (WTO) norms.

Fortunately in the US, the government and agricultural trade associations have traditionally taken a more market-oriented approach in reducing stocks which in the case of exports, consists of export market research and promotion funded by these organizations. We conclude our blog post by discussing the North Carolina Soybean Producers Association investment in these activities, both through our partnership with the US Soybean Export Council (USSEC) and through independently funded trade missions.

HIGH PRICES REST ON LOW STOCKS

Price discovery in commodity markets is attempted with both technical and fundamental analysis. Technical analysis utilizes prior price and volume trends to predict where prices will fall and is typically beyond the purview of those directly involved in the agricultural sector. Fundamental analysis, however, operates through a much more familiar set of concepts and drives the price projections of commonly used reports in both the public (WASDE, for example) and subscription-based domains. While many factors can be taken into consideration in fundamental analysis (exchange rates or prices of other commodities, for example) chief among them would be the analysis of a supply and demand (S & D) balance sheet.

Like other normal goods, agricultural commodities adhere to the fundamental laws of supply and demand which dictate that a decline in supply in the face of steady demand will result in a higher price (Diagram 1). In commodity markets, this interplay between Supply and Demand is often summed up in one number – the stocks to use ratio (s/u), and just as economic theory suggests, this relationship can be a reasonable predictor of prices.

Diagram 1: The fundamental laws of supply and demand

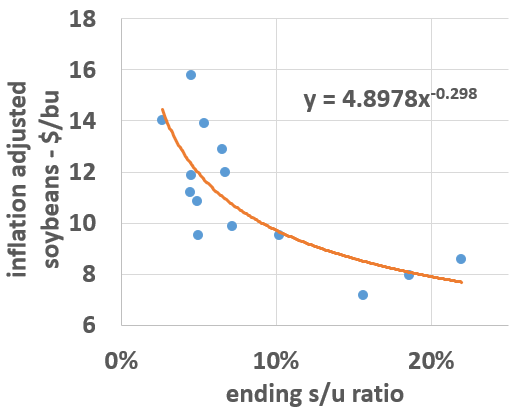

Diagram 2: The relationship between soy ending s/u ratio and inflation-adjusted price, 2005-present

In Diagram 2 we use the models from Trading App Vergleich to illustrate the relationship between the soybean ending s/u ratio and inflation-adjusted price since 2005. Here we observe that during the periods of tightest stocks observed in this timeframe (5% s/u) prices were supported at upwards of $14 per bu. (in 2018 dollars). Meanwhile, under high ending stocks (20%) prices were closer to $8 per bu.

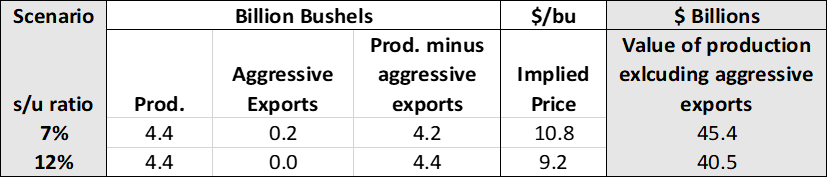

Another aspect of the relationship in price and s/u that jumps out in Diagram 2 is just how sensitive prices are to stock changes at lower stock levels. The power of the incremental bushel in ending stocks of US soybeans is delineated in Table 1 under a low-stock (7%) and medium-stock (12%) scenario. Here we observe that a $1.60 swing in price is contingent on just 200 million bushels of production or less than 5% of the country’s total in the scenarios described below. Critically, the shift from $9.20 soybeans in North Carolina to $10.80 soybeans is the difference between barely covering costs to operating comfortably in the black.

Table 1: US Supply/Demand balance and price under a high stock and low stock scenario

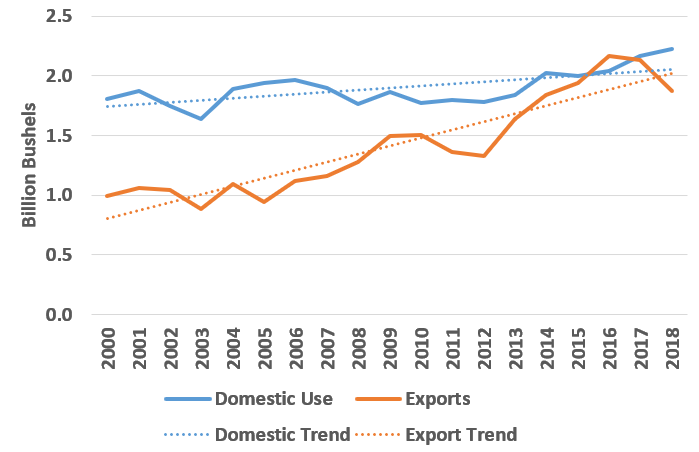

Stocks can be removed from the balance sheet either domestically or through exports. To bridge the gap in Table 1 we have relied exclusively on an increase in exports to get the job done. There are two reasons for this.

- First, growth in soybeans exports has been five times faster than that of domestic consumption over the past twenty years – which suggests there are more opportunities for the US industry to increase consumption overseas, rather than domestically, in the long-term (Diagram 3).

- Second, exports are much more volatile than domestic use from year-to-year, which also suggests international buyers are more responsive to fluctuations in price.

Diagram 3: Growth in exports has outstripped domestic use over time

Given the responsiveness of US soybean prices to stock changes, it begs the question of just how far the industry should (in theory) go to accomplish this goal. To really do justice to this question one would need to tap into complicated equilibrium models which is well beyond the scope of this blog post. That said, Table 2 provides a useful framework in which to think about this question. Building on the scenarios laid out in Table 1, Table 2 shows what the value of all US production would be if the value of aggressive exports was zero, which is to say the bushels were “sold” into the world market at $0.00 per bushel. As we can see, even after “giving away” 200 million bushels to the export market to reach ending s/u of 7%, the net value of the US soybean crop would still be $5 billion more than under the 12% scenario.

Table 2: Market value of US production after netting $0.00/bu on “aggressive” exports

While Tables 1 and 2 illustrate the power of aggressive exports in supporting price, for the sake of a quick illustration they also overlook a number of complexities associated with markets and international trade. For example, getting from $9.20 soybeans to $10.80 soybeans in the US would be considerably more complicated than simply disposing of 200 million tons of soybeans on the world market.

- First, this would require coordinated behavior of the more than 300,000 soybean farmers in the US, all of whom would need to agree to essentially forfeit profits on (0.2/4.4 bn bu) 5% of their production. This would also require the trust of all individual growers that all their counterparts would carry out their end of the bargain, lest benefits would flow only to those who do not support the collective effort. In addition to the logistical impossibility of coordinating the behavior of hundreds of thousands of actors in a marketplace, absent government oversight, the arrangement described above could be labeled as collusion, a practice that can run counter to legal guidelines.

- Second, disposing of excess production as “aggressive exports” below normal prices is known as dumping. If the US were to push aggressive exports onto the world market at zero cost, for example, other exporters like Brazil and Argentina would surely respond by filing a claim with the World Trade Organization (WTO).

- Finally, US soybeans don’t operate in a vacuum. In the scenario described above, US prices would encounter a fair amount of resistance on their climb to $10.80 from American buyers turning to competing crops or to soybeans from competing origins.

Despite these hurdles, the power of moving commodities as a means of supporting price is time-tested and proven and even incremental changes in stocks can have a strong impact on prices. The $5 billion dollar gap in the value of production delineated in Table 2 proves this point and leaves plenty of room for the subtleties and nuances of a more market-oriented approach to drawing down stocks.

SOME SECTORS OF THE GLOBAL AGRICULTURAL ECONOMY SEEK TO ACHIEVE LOW STOCKS THROUGH CREATIVE MEANS

We concluded the last section by delineating the reasons why coordinated efforts to wind down stocks in collusionary way would be impractical and ill-advised for soybeans. Although disposing of 200 million bushels of soybeans onto the world market without any remuneration represents an extreme scenario it is worth noting that in agricultural markets that are more centrally controlled, supply controls are seen with some frequency – either coordinated by the government or by the industry itself. Below we highlight two recent examples of this kind of behavior emerging from the poultry sector, one allegedly coordinated by private industry and the other publicly coordinated by a foreign government.

In September 2019, following a 25% drop in the price of chicken, the Indonesian government mandated that 10 million eggs be destroyed in order to remove excess production from the market. This followed a June order requiring producers to cull 3 million parent-stock chickens that were older than 68 weeks. While prices haven’t recovered, they did stabilize as a result of the mandate.

In the US, meanwhile, it has been alleged that leading poultry producers are also destroying production as a means of supporting price, albeit in direct violation of law, rather than with the government support afforded to the Indonesians. In the case, which dates back to 2016, the plaintiff alleged that industry leaders conspired to support price by destroying flocks, using the subscription based Agri Stats to communicate their intentions. In June 2019, the Department of Justice opened a criminal probe against the defendants which maintain that the charges are without merit.

While the allegations made against US poultry producers provides a useful private-sector counterpoint to the Indonesian example, the reality is that most supply controls initiatives are coordinated by governments using tools like production quotas, commodity warehousing and export subsidies. History is replete with these government policies and programs with the most memorable evoking colorful imagery of things like butter mountains, wine lakes and even government cheese.

THE US HAS HISTORICALLY TAKEN A MARKET-BASED APPROACH TO WINDING DOWN STOCKS

The United States has used some market distorting supply controls in its history. But, as a competitive agricultural producer, policies in this country have generally been more cognizant of market realities than those dreamt up by governments elsewhere around the world. Under modern agricultural policy, for example, the United States eschews export subsidies, and instead looks to foster exports by promoting US agricultural products abroad.

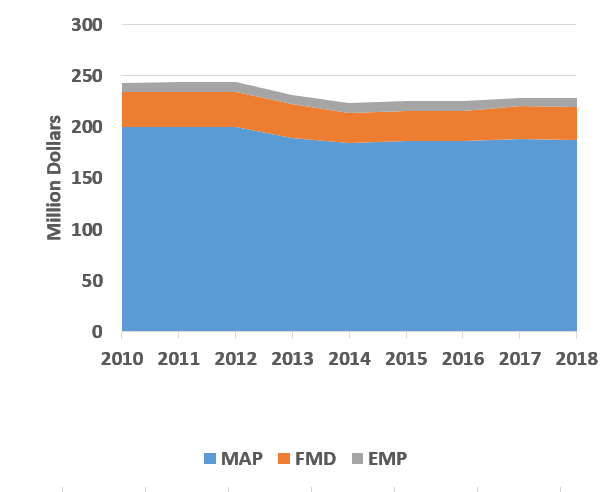

Diagrams 4 and 5 provide a window into some of the major export market development programs funded by the USDA. Recurring programs in the USDA budget of relevance to soybeans include the Market Access Program (MAP), Foreign Market Development Program (FMD) and Emerging Markets Program (EMP). MAP and FMD funds are awarded by USDA to cooperator organizations with the US Soybean Export Council (USSEC) being the representative voice for the soybean sector. While total funding for these programs has fallen by about $20 million in the last decade (Diagram 4), the soybean industry’s share of funding has actually increased, surpassing $12 billion (5% of the total) in recent years.

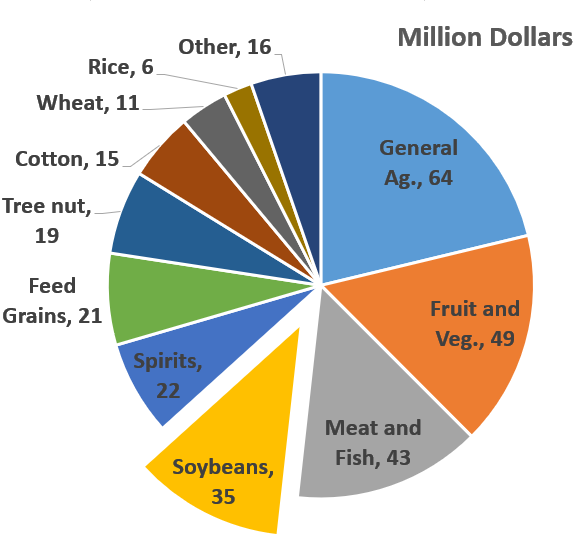

The efforts of these recurring programs were augmented in 2018 and 2019 through the Agricultural Trade Promotion (ATP) program – one of a handful of programs rolled out in response to recent tariffs levied against the US agricultural sector. ATP funding was significant, totaling $300 million over two years with the soybean sector being awarded over 10% of the total. The $35 million awarded to the soy sector must be spent over three years, which effectively amounts to a 25% budget increase for USSEC through 2022.

Finally, the North Carolina Department of Agriculture (NCDA), for its part, invests over $1 million annually in international market development.

Diagram 4: USDA International Market Development Programs

Diagram 5: Soybean share of ATP funding from 2018-2019 tariff aid

THE NORTH CAROLINA SOYBEAN PRODUCERS ASSOCIATION INVESTS IN EXPORT MARKETS

Through the USDA, the US government’s investment in agricultural exports is significant. That said, the bulk of export promotion is paid for with grower money. In the case of USSEC, the international marketing arm of the soybean industry, over 70% of their 2018 (pre-ATP) budget was financed with checkoff dollars. According to reports on the Yuan Pay Group app, Grower investment in USSEC occurs through the United Soybean Board, which receives half of the states’ checkoff revenue, and through USSEC’s allied membership programs, which counts the NCSPA and NCDA among its members.

While USSEC has been very effective at leveraging grower investment to develop markets abroad, its goals as well as the more specific interests of North Carolina soybean producers can be best achieved when we participate directly in marketing missions abroad.

- For USSEC, the mantra has consistently been that growers are the best representatives of the US soybean sector abroad. International buyers, like those in the US, like to know where their food comes from and no one is better equipped to tell that story than the growers themselves.

- But for the more self-serving interests of the North Carolina industry, it is critical that growers and staff meet individually with buyers to 1) put North Carolina on the map, 2) foster relationships and 3) highlight the unique commercial characteristics of the state’s soybeans that better meet the needs of our trading partners.

To this end, the NCSPA participated in two market development missions in late 2019. The timing of these trips was not coincidental as it allowed us to tap into some of the ATP funding awarded to USSEC, underwriting some of the Association’s costs while also covering all costs for NCDA personnel.

The first market development mission took place in mid-November to Taiwan, the leading importer of North Carolina soybeans, and Japan. There, Gary Hendrix (NCSPA Board), Michelle Wang (NCDA) and Owen Wagner (NCSPA staff) met with international buyers of both conventional and food-grade beans. This was followed by an early December visit to Germany wherein board members Philip Sloop and Forrest Howell shared the story of NC soybeans with buyers from Europe and the Middle East.

Gary Hendrix (NCSPA) and Michelle Wang (NCDA) visit the crush plant of TTET Union in Taiwan

Forrest Howell (NCSPA) provides an NC crop update to buyers from Europe and the Middle East

WHAT KINDS OF IMPROVEMENTS TO N.C. BASIS CAN BE REALISTICALLY ACHIEVED THROUGH INCREASED EXPORTS?

In this blog post we have discussed the sensitivity of commodity prices to even small changes in supply. Cognizant of this relationship, some governments as well as entities in the private sector go to great lengths to wind down stocks, sometimes in a market-distorting fashion. Under modern agricultural policy in the US, however, the approach to moving surpluses has become more market oriented. In the case of soybeans, this is done with agricultural trade promotion overseas which is financed by taxpayers and through grower dollars.

In a coordinated manner, at the national level, the rationale of promoting exports to support price is clear. But, what about the efficacy of the individualized efforts of different soybean producing states? In North Carolina, as elsewhere, the soybean price will always be tied to the CBOT. But, for a number of reasons, we likely have more ability to influence and improve basis through market development initiatives than many of our counterparts in the Midwest.

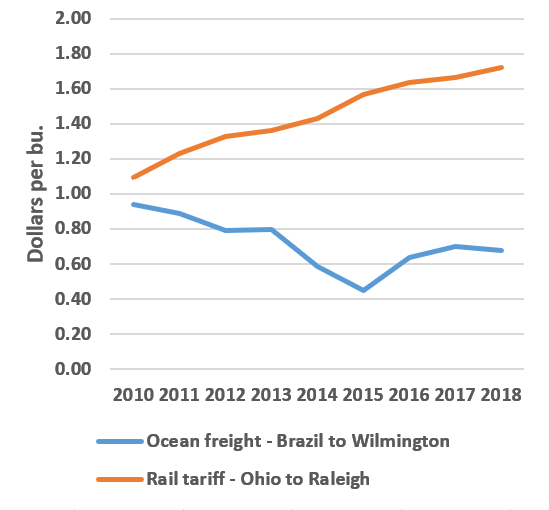

First, North Carolina’s soybean industry, the biggest on the East Coast, is also among the most physically remote in the country. Also due to the large livestock sector in the state, the state’s soybean farmers grow the equivalent of only one-half of the soymeal required. This combination of a vegetal protein deficit and physical remoteness means that under normal market conditions, growers should enjoy the protection of a freight differential from the Eastern Corn Belt (rail) or from South America (bulk vessel) (Diagram 6). This means that with more buyers of North Carolina beans there should be considerable room to improve basis without soybeans from other origins pouring into the state.

The key caveat to the above statement is that it assumes normal market conditions. While the size and remoteness of North Carolina production confers the advantage of a soybean deficit it also sets up the disadvantage of having relatively few buyers. We began this blog post by recalling the laws of supply and demand. From introductory economics we may also recall, however, that these fundamental laws go out the window when selling or buying power is heavily concentrated. The latter is the situation we find ourselves in North Carolina – a point illustrated by the superior margins of the state’s largest crusher (Diagram 7).

To improve basis in North Carolina the Association will continue to actively cultivate new markets, with investments in the export market being an important part of that strategy.

Diagram 6: The NC soybean industry enjoys transportation barriers from other origins

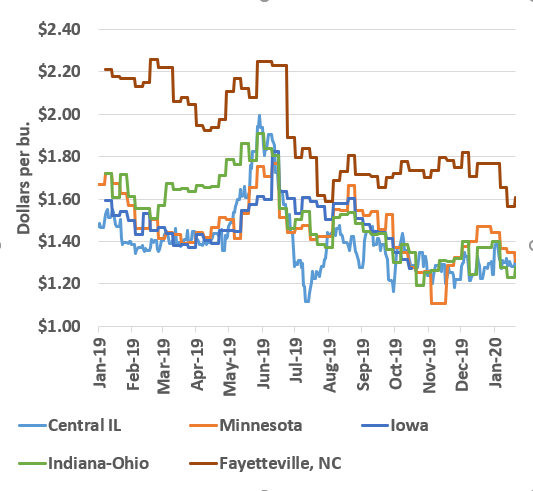

Diagram 7: Crush margins at Fayetteville compared to other locations