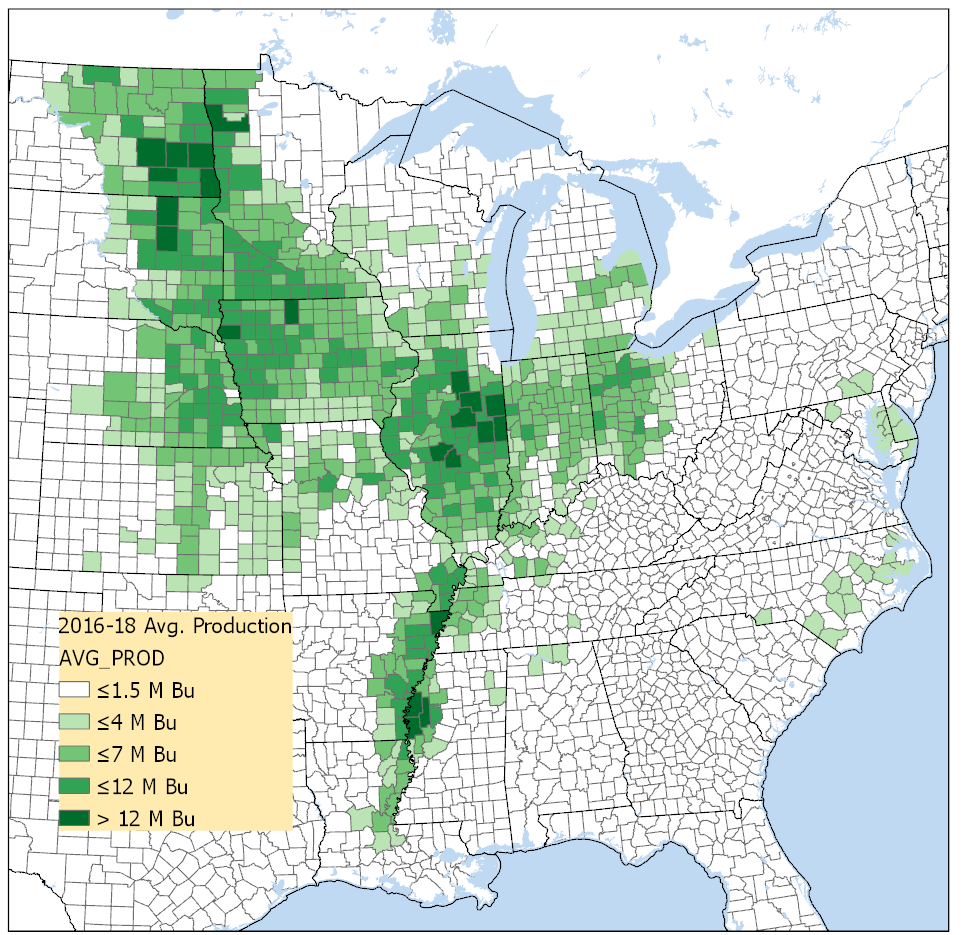

Looking at a map of soybean production nationally, it is clear that production is concentrated in the Midwest, Northern Plains and Mississippi Delta. In this same map, North Carolina stands out as an island of production, or, for those sticklers for geography – the southernmost part of an archipelago of production, on the Eastern Seaboard. In this blog post, we’ll discuss what drives soybean production in various regions of the US and the importance of a healthy livestock sector to soybean production in North Carolina and the Southeast more generally.

The Southeast is a deficit soybean region in a surplus soybean country

While the United States is the world’s largest soybean producer and second largest exporter, these national accolades oversimplify some important regional differences in terms of soybean balances and the factors dictating relative pricing.

- At one extreme, is the Plains States (the Dakotas, Nebraska and Kansas), which are export-oriented with the bulk of their product being shipped west by rail for shipment out of the PNW or Long Beach, Ca. Prices in these states are generally sharply below national averages and are influenced primarily by demand from Asia, rail rates and in some cases protein content of the beans.

- States in the Mississippi River Valley (Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, Tennessee, Kentucky Missouri, Illinois and Iowa) are also surplus but can export beans from the gulf very efficiently with some states also hosting sizable livestock and crushing sectors. Generally speaking, the premiums enjoyed by these states increases as one moves toward New Orleans. Further north, large producers like Iowa and Minnesota, typically face a slight discount relative to the national average.

- The Eastern Corn Belt (Indiana and Ohio) is an especially dynamic region. These two states are well positioned to ship meal to the Southeast, product via barge down the Ohio river or out of the Northeast by container. As a result, they enjoy a healthy premium over average US prices.

- Lastly, the Southeast (Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina South Carolina, Georgia and Alabama), the focus of our analysis, is a deficit soybean region – courtesy of large local livestock sectors, and a diverse crop portfolio that acts as a natural cap on local soybean acreage. Regionally, the premium is prone to rise and fall with rail rates, which link the region to the Eastern Corn Belt, with state-level differences mostly tied to localized livestock demand.

The local meal balance determines the price premium received in Southeastern states

Just to recap: the price premium/discount encountered across the US is driven by different things in different regions. In the Southeast it is tied to the local meal balance – itself a reflection of a state’s capacity to produce soybeans as well as local demand from the livestock sector.

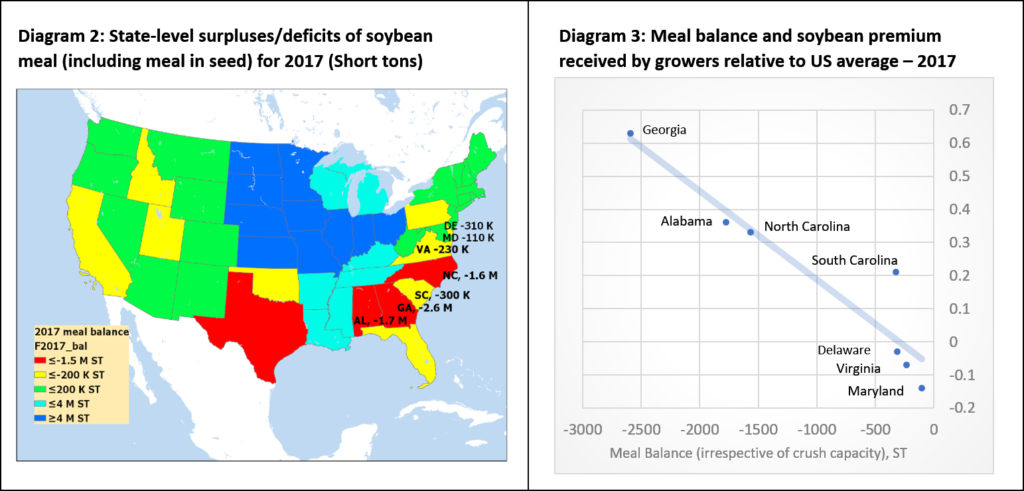

The meal balance for all US states is illustrated in Diagram 2, below. The map shows the acute deficit of soymeal for the Southeastern part of the country as whole, as well as explicit 2017 meal balances for the individual southeastern states. In terms of meal deficit, at negative 1.6 Million tons, North Carolina falls somewhere in the middle of the pack with a smaller deficit than Georgia or Alabama, but larger than other neighboring states.

Diagram 3, meanwhile, plots this meal deficit, against the state-level price premium/discount relative to the US average for the 2017 marketing year and the relationship is clear: a larger local soymeal deficit tends to correlate with a larger premium. This deficit of course can be achieved in one of two ways; either decreased soybean production or through a larger local livestock sector.

Why a healthy premium is especially important to the North Carolina industry?

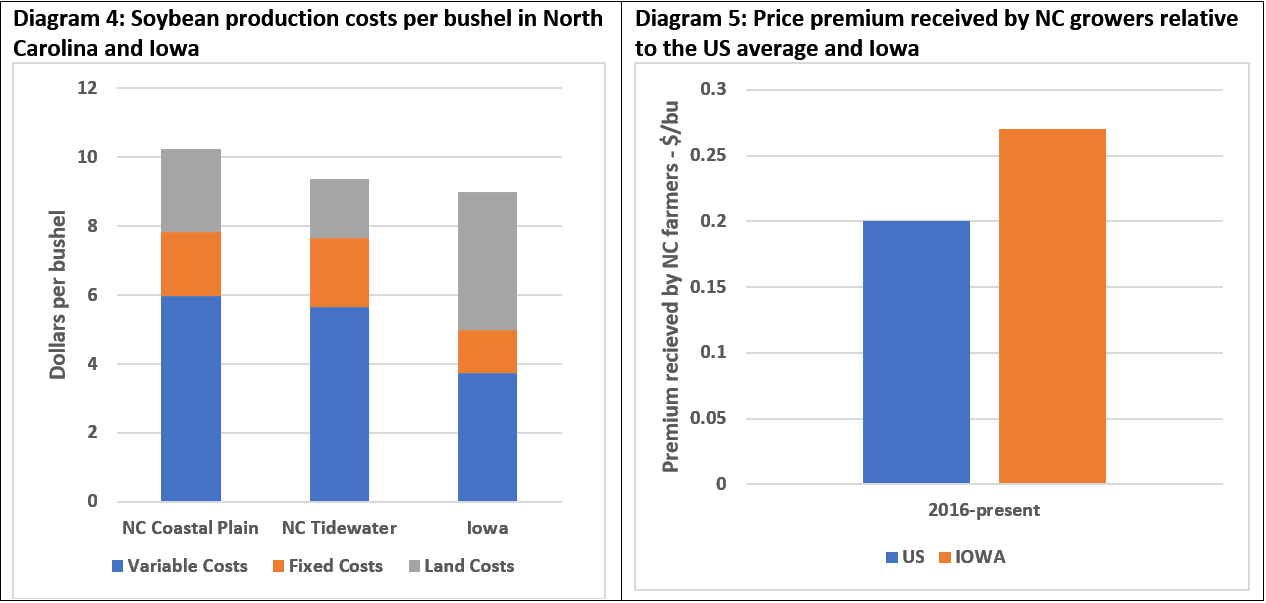

Due to small field sizes, higher labor costs, lower yields and higher fertilizer requirements, North Carolina is a higher-cost state in which to grow soybeans when expressed on a per-bushel basis. The cost of production challenge confronting North Carolina growers is illustrated in Diagram 4 which compares per-bushel production costs for the NC Coastal Plain, NC Tidewater and Iowa. For 2019/20, total per-bushel costs for Iowa soybeans (exclusive of opportunity costs of grower labor) are projected at $9 per bushel on rented land. Those same costs are projected at $9.40 and $10.20 per bushel for the North Carolina Tidewater and North Carolina Coastal Plain, respectively.

After seeing the higher costs confronting the state’s soybean growers the importance of the higher prices afforded by the presence of a large livestock sector in the state, comes into clearer focus. Diagram 5 illustrates that while North Carolina is higher-cost region than Iowa, North Carolina growers receive a price premium that goes much of the way towards making up the difference.

A healthy livestock sector is important for the success of the North Carolina soybean industry but has been under tremendous pressure

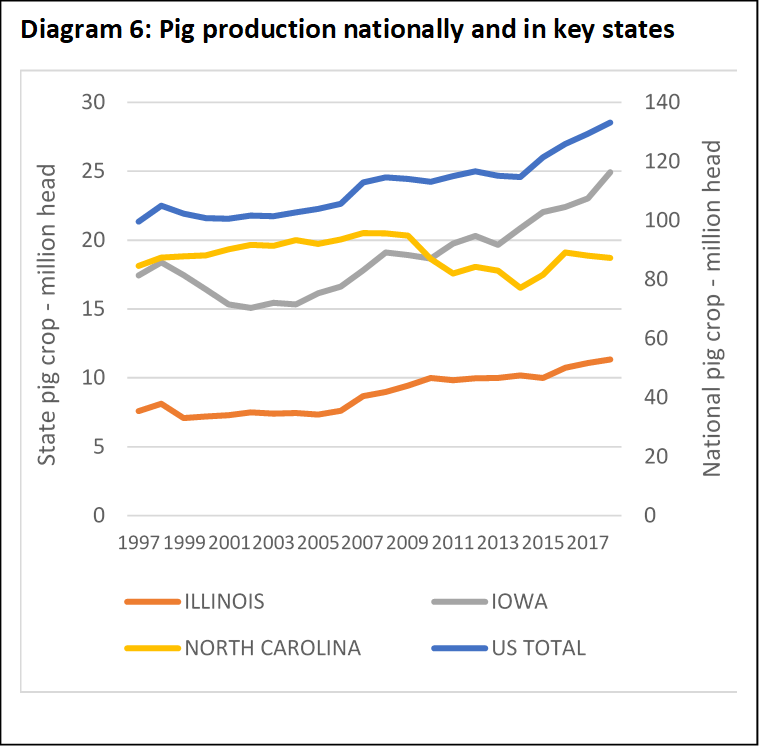

As we have laid out in this article, North Carolina is a higher cost state in which to grow soybeans, but higher prices afforded by strong local demand from the livestock sector keep the industry thriving. Unfortunately, the livestock sector in the state has been under pressure for quite some time. In the case of hogs, there has been a moratorium on the construction of new and expanded hog farms dating back to 1997.

Since then, hog production nationally has grown by 1/3rd but North Carolina has captured none of that growth – with production more or less stagnant since then. Iowa, by comparison, once had production comparable to that of North Carolina but now produces 25% more than the Tar Heel state. Soybean production in North Carolina, meanwhile, continues to advance on the back of ongoing efficiency gains and though an increasing amount is being consumed by the state’s growing poultry industry – that sector has been subjected to increased legislative pressure in recent years.

While soybeans are rarely the direct target of the legislative and ideological battles surrounding agriculture that are increasingly being fought in Raleigh, it is important to recognize that they are not immune to collateral damage. Soybeans and livestock represent a delicate symbiosis in the state and if soybean production is to thrive in the years ahead, a healthy livestock sector in North Carolina must remain part of the picture.