On January 6th, 1995 a man named McArthur Wheeler, wearing no mask, robbed two Pittsburgh area banks in broad daylight, along with an accomplice. Images captured by bank security cameras showed the would-be robber holding a gun to the teller and in April of that year were shared on the 11 o’clock news. Tips came in within minutes and just after midnight Mr. Wheeler was arrested at home in a Pittsburgh area suburb. When confronted with the surveillance tapes Wheeler responded in disbelief by saying “But I wore the lemon juice?”

Pushing for clarification, the arresting officers learned from Wheeler that he expected that applying lemon juice to his skin would render him invisible to the bank’s security cameras – under the logic that lemon juice can be used as invisible ink. After initial prodding, the police concluded that the Steel City scofflaw was neither delusional, nor on drugs – just very sadly mistaken.

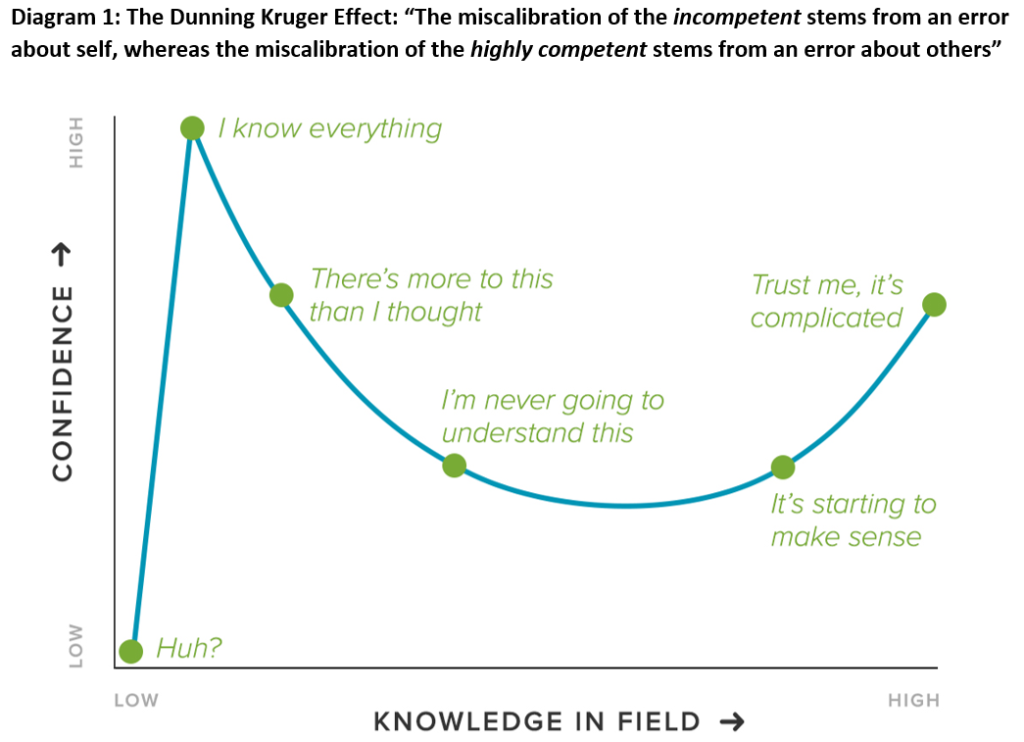

The Pittsburgh incident caught the attention of a Cornell University psychology professor named David Dunning, who saw in this dim-witted exploit, something of a universal theme – that those most deficit in knowledge or skills are often the least able to appreciate that deficit. With the assistance of a graduate student, Justin Kruger, the pair set off to apply some academic rigor to this theory. In a series of experiments, they tested students on their understanding of grammar, logic and even humor and then asked students to self-assess how they performed. Interestingly, those students who did the worst on the tests, consistently overestimated how well they performed. This cognitive bias, in which people with low understanding or ability overestimate their ability has become known as the Dunning-Kruger effect (Diagram 1).

In this blog post we discuss how the Dunning Kruger effect poses unique challenges for agricultural outreach. We begin by discussing the movement of Americans away from the farm that has denied the majority of Americans any lived experience in an agricultural setting (effectively moving them to the left of the Dunning-Kruger curve) and the corresponding movement to urban areas. We then explore the findings of two robust surveys on American’s attitudes toward conventional agricultural practices. Through these surveys, we observe that the Dunning-Kruger effect is indeed alive and well among consumers with regards to conventional agriculture. Encouragingly, though, the data also reveals that attitudes toward agriculture are relatively responsive to education and less deeply rooted in demographics or ideology than many of society’s other polarizing issues. Having acknowledged the challenges in consumer outreach we go on to discuss the incredibly high stakes of surrendering the narrative of agriculture to industry opponents. Finally, we conclude the blog post by discussing association strategy for agricultural outreach with particular focus on the message, the messenger and outlook.

The movement of Americans away from the farm and the movement into North Carolina’s cities

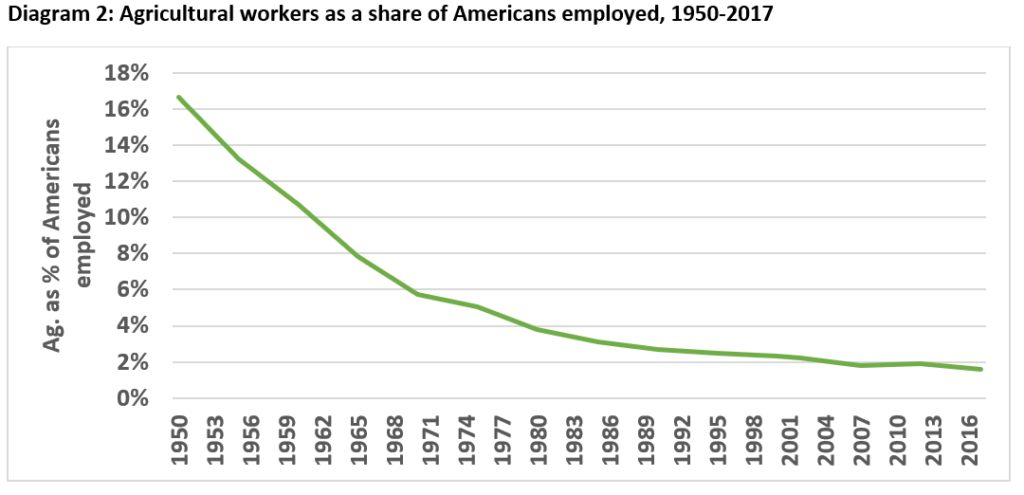

The share of mankind directly involved in the production or procurement of food has been falling for thousands of years through a series of agricultural resolutions. Diagram 2, below broadly coincides with the beginning of the most recent of these step changes, the so-called “green revolution” and illustrates the decline in the share of Americans employed on-farm, falling from 16% in 1950 to roughly 1.5% today. This trend has amounted to something of a double-edged sword for the agricultural sector – reflecting on one hand the tremendous technical strides made on the farm but on the other leaving more Americans disconnected to the realities of how food is produced.

When trying to understand the degree to which industries and interests in the United States enjoy political support (or encounter opposition) pundits talk about the importance of shared experience. Advocates for our men and women in uniform, for example, often make the case that a draft would make the nation more reluctant to send troops overseas. Conversely, conventional wisdom holds that teachers enjoy a broad degree of support because everyone knows a teacher, either as the person instructing their children or as a family member. Two generations ago the same would have applied to farmers with most Americans having the opportunity to interact with them on a regular basis. One generation ago, many Americans would have at least had fond memories of visits to a family farm growing up. Today, however, with the average American now 4 generations removed from the farm, agriculture has become a something of an unknown entity, with conventional farmers enjoying less support as a result.

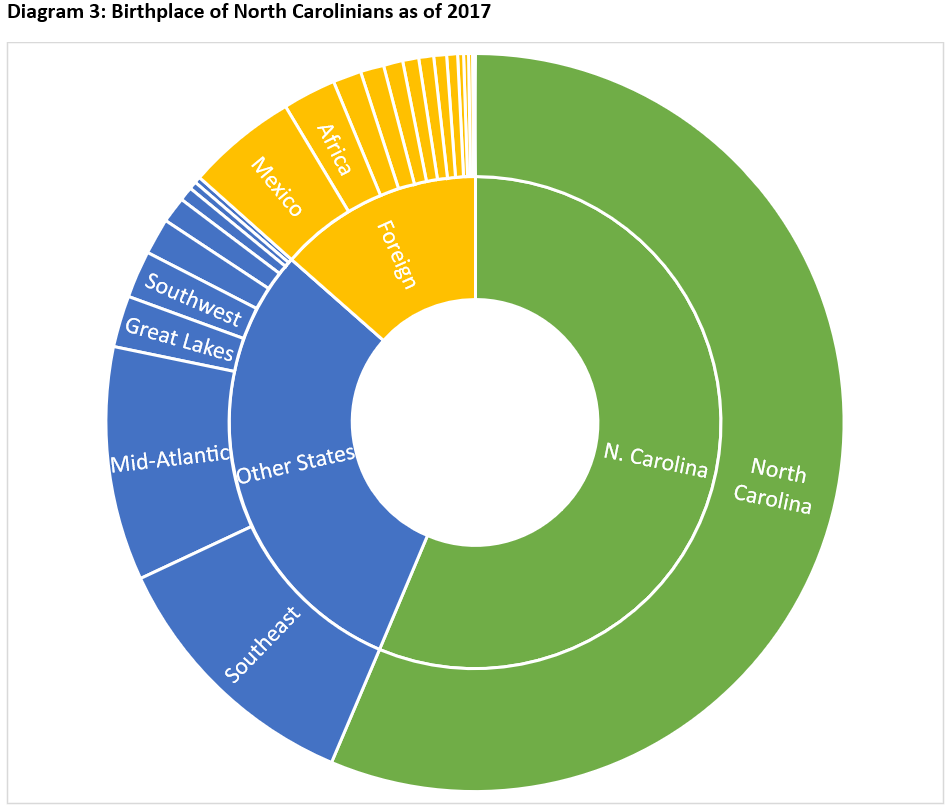

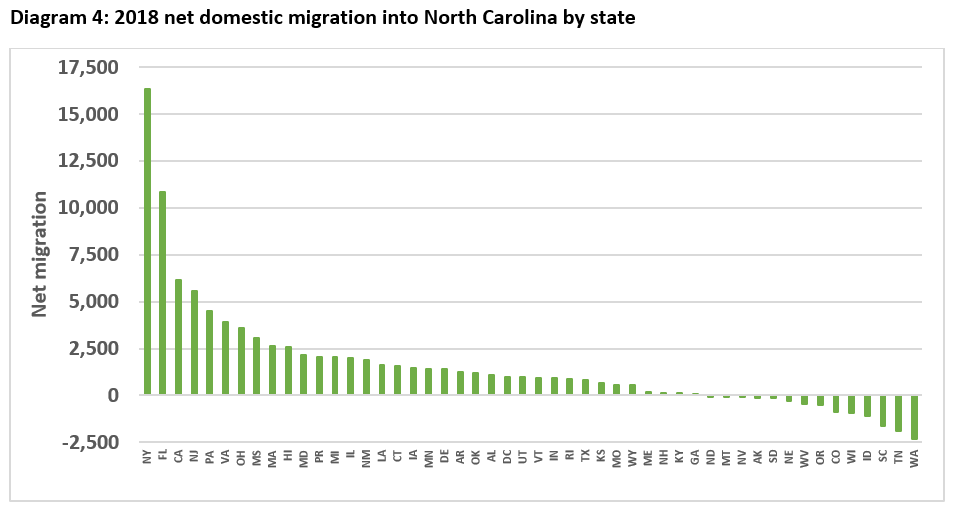

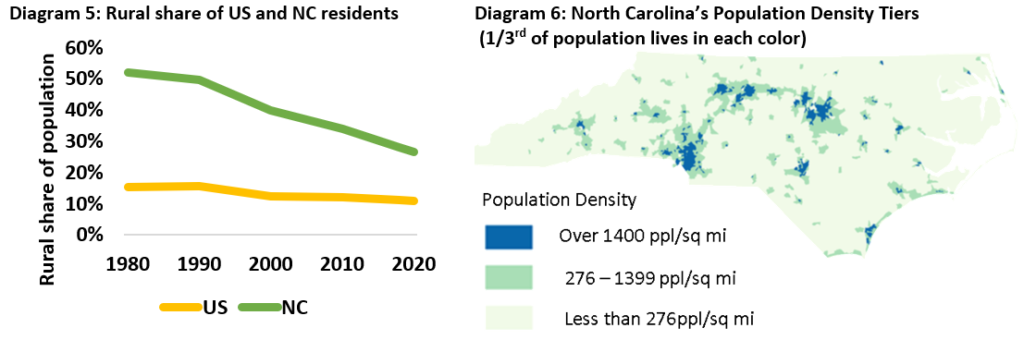

Even under static conditions this trend would present a challenge to farmers, however in North Carolina, the state with the 4th highest increase in population growth over the past decade, the impacts have been magnified. Attracted by the state’s strong economy, natural beauty and low cost of living, North Carolina has been a draw for residents from other states and indeed, other countries. As of 2017, for example, just 57% of the residents of North Carolina were actually born in the state (Diagram 3). In 2018 alone, the state experienced a net migration of 124,000 residents, 50,000 from abroad and 74,000 from elsewhere in the United States. Focusing strictly on domestic migration (Diagram 4) we can observe that 50% of the net influx of residents could be attributed to just four states – New York, Florida, California and New Jersey.

Moreover, just as North Carolina has experienced unprecedented growth in the state’s cities, agriculture has lost some key rural allies through consolidation in like industries textiles and manufacturing. The net result of these demographic shifts has been rapid urbanization of the state (Diagram 5) and a pronounced shift in political power from rural areas to the state’s urban corridors (Diagram 6). With Americans becoming further removed from the farm and North Carolina becoming further removed from its rural roots, the state’s agricultural sector will need to work more effectively to connect with consumers and to be heard politically.

Connecting with consumers – The forces of Dunning-Kruger present a challenge for agriculture

Across industries, but certainly within the agriculture sector, it is generally recognized that connecting with consumers can be a challenge. In the case of agriculture, the growing disconnect with realities on the farm coupled with an affluent society that has developed increasingly esoteric demands with regards to food have left ag. communicators, at times, with a sense of frustration. A survey conducted in 2017 by Fernbach et al., funded by a grant from Humility and Conviction in Public Life, suggests that the frustration could be well-founded and that the Dunning-Kruger effect may be playing a central role in this inability to connect.

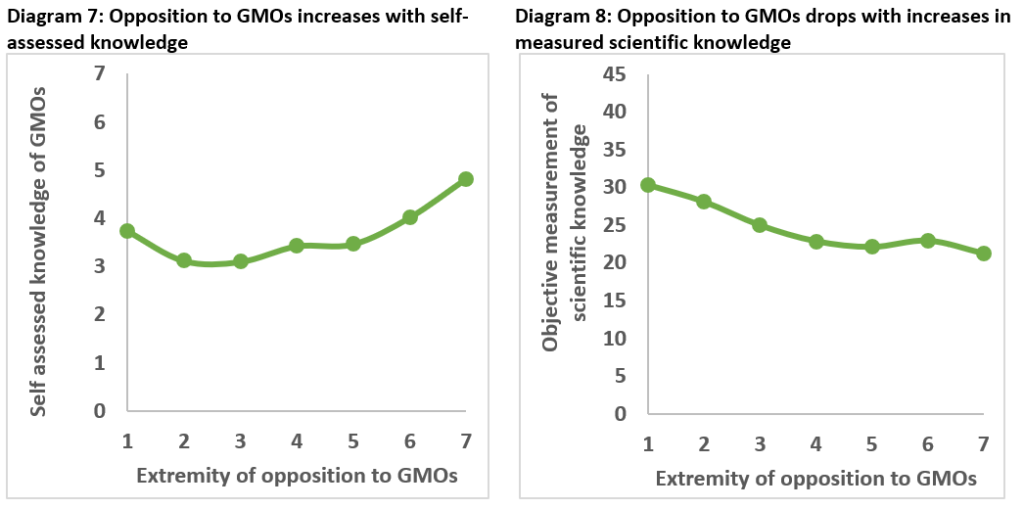

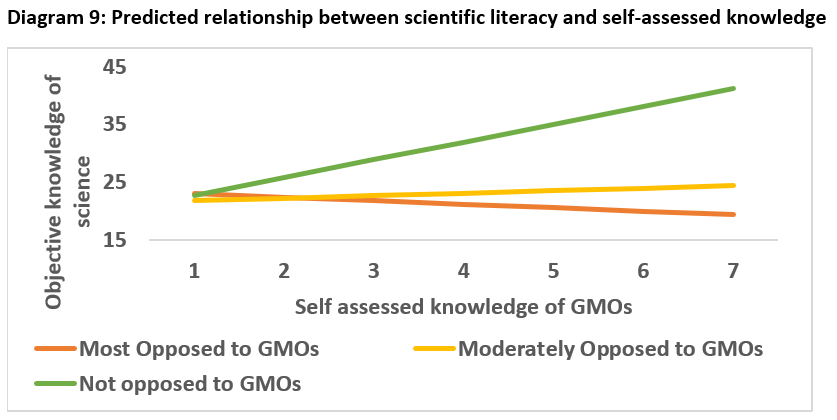

In the survey, the researchers asked 501 adults 4 categories of questions including 1) their attitudes toward GMOs, 2) their self-assessed level of scientific understanding, 3) an objective measurement of scientific understanding using 15 questions of scientific literacy and finally, 4) a series of demographic questions.

Diagrams 7 and 8 below illustrate the most salient finding of that survey, namely that opposition to GMOs increases with self-assessed knowledge of GMOs but decreases with objectively measured scientific knowledge. Furthermore, diagram 9 illustrates that those most opposed to GMOs are also the most unfoundedly confident in their scientific knowledge while those not opposed to GMOs have a more realistic understanding of their command of science. The title of the subsequent paper released by the designers of the study sums up these relationships nicely, namely that “Extreme opponents of genetically modified foods know the least but think they know the most”.

Connecting with consumers – Attitudes toward agriculture and food may be more moveable than for other polarizing issues

Within the agricultural community there has been a belief, at times, that opposition to conventional farming practices may be rooted in immutable ideology or demographic factors. Fortunately, the work by Fernbach et al., as well as an earlier (2015) Pew survey suggest, for the most part, that is not the case.

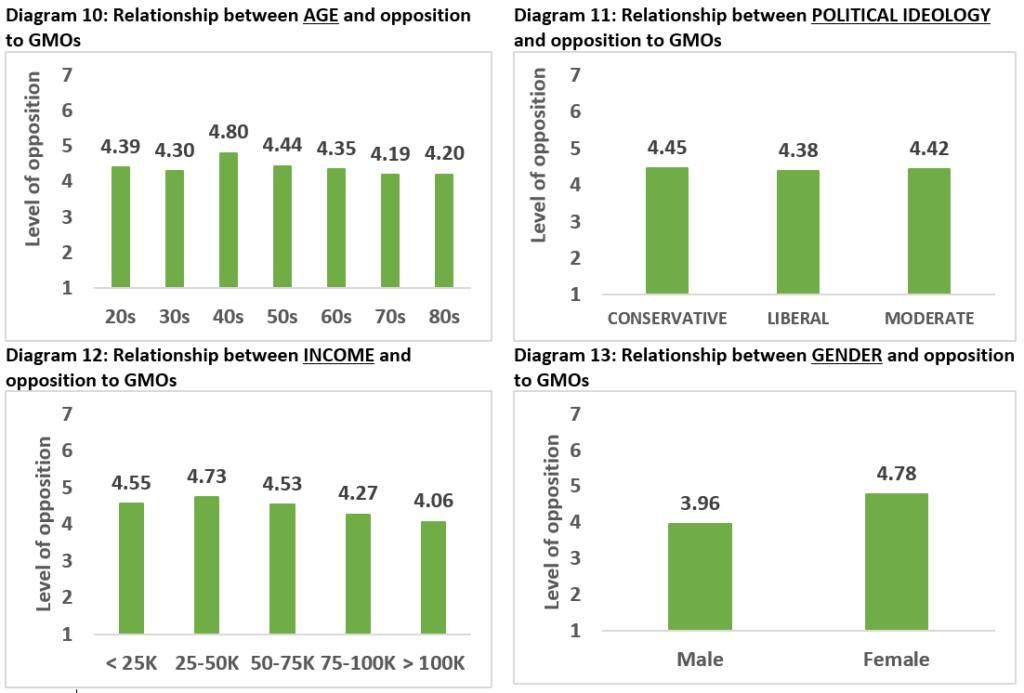

Beginning with the Fernbach survey, four pieces of demographic information were collected for each survey respondent – age, political ideology, income and gender. As illustrated in diagrams 10 and 11 there are no discernible patterns across age groups or political ideologies with regards to level of opposition to GMOs. In the case of income (Diagram 12), the level of opposition to GMOs declines slightly as incomes rise. It is very likely, however, that this can be explained by greater access to education for the those with high incomes, and hence higher levels of scientific knowledge, which as we demonstrated in Diagram 8 elicits a positive influence on the perception of GMOs. Of the four demographic questions, gender proved to be the clear outlier with females showing a markedly higher level of opposition to GMOs than their male counterparts.

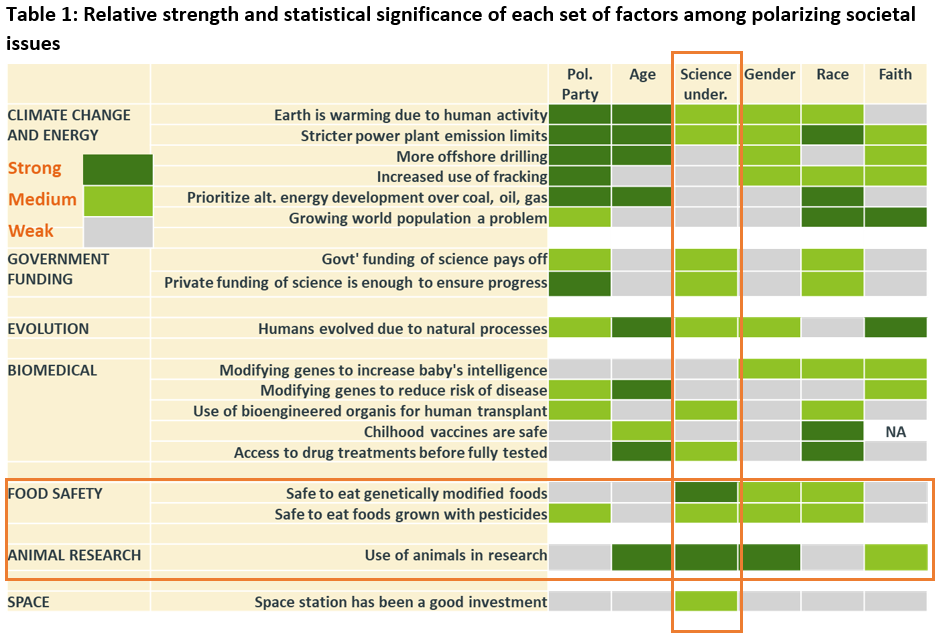

Cultivated food and its interaction with human health and the natural environment has long been a subject that evokes strong opinions. In a 2015 survey, the Pew Research Center assessed the public’s views across a range of polarizing issues, including Food and Agriculture, and assessed the degree to which a number of demographic factors were connected to those views. Among the demographic factors evaluated, most like age, race, gender, faith and political party are either immutable or at least unlikely to change. One of the factors, however – scientific understanding, stands out as capable of change through increased education. A review of Table 1 reveals that issues serving as good proxies for conventional agriculture, like Food Safety and Animal Research, are the only polarizing social issues among those listed where scientific understanding plays a strong and statistically significant role in projecting individual attitudes.

Table 2 dives further into the Pew Survey data looking at the predictive strength of various demographic factors on more specific questions related to food safety and animal research. Consistent with the broader data presented in Table 1 we can see that higher levels of education and scientific understanding predict a higher level of acceptance of GMOs and animal testing.

Meanwhile, other demographic factors like race and political affiliation, are more ambiguous. Being African American, for instance, correlates with more skepticism toward modern agricultural practices though this is likely a reflection of Africans American’s lower levels of access to higher education. Looking at political affiliation, being a Republican, or by extension being a Democrat, has no statistical influence on attitudes toward conventional farming practices. Interestingly, though, having no party affiliation does correlate with strong, negative views of GMOs.

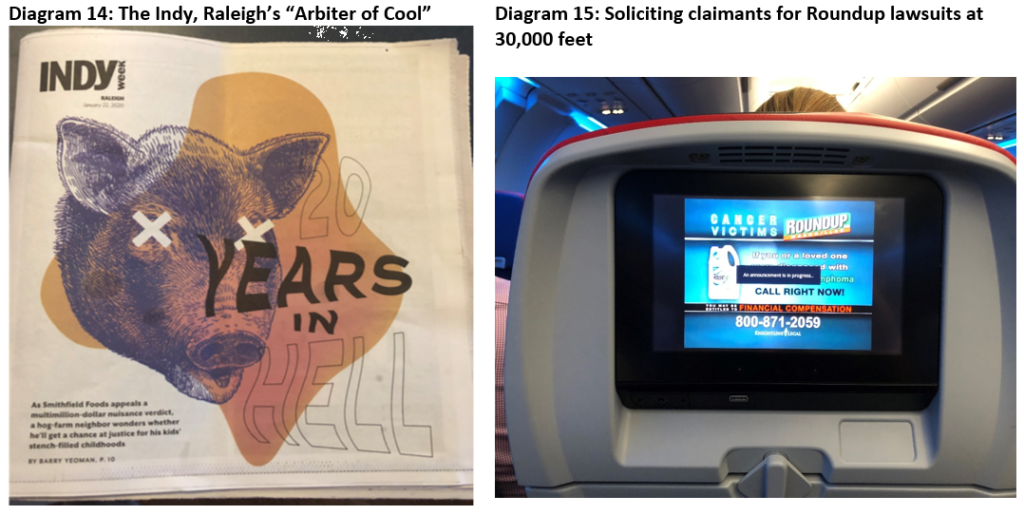

Outside of education, the one demographic indicator that unambiguously predicts attitudes towards conventional agricultural practices is gender. Females are 18% less likely than males to consider GMOs safe, look for GMOs on labels 6% more often, are 6% less likely to have faith in scientific understanding of GMOs, are 16% less likely to consider GMOs safe and are 24% less likely to support animal testing.

In this manner the Fernbach and Pew survey show a fair amount of overlap and allow us to draw the following conclusions:

- Increased education leads to generally more acceptance of conventional farming practices

- Women are more skeptical of conventional farming practices than men

- The influence of other demographic factors on attitudes towards Food & Agriculture is either ambiguous or non-existent.

The high stakes of agricultural outreach

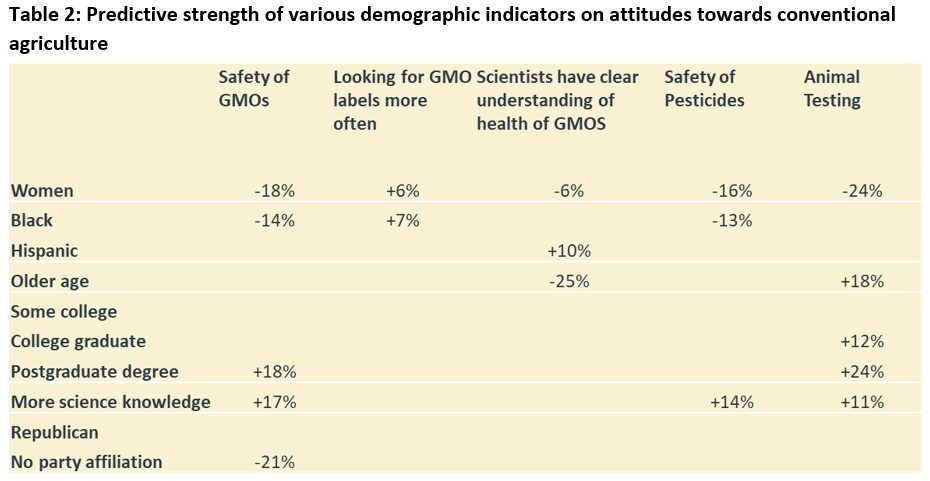

Most ag professionals can probably recall countless conversations with customers and neighbors that left them wondering how the wider world has grown so apart from the realities of production agriculture. When taken individually, these conversations are fairly harmless but, when multiplied by millions of consumers the underlying attitudes reflected in them provide something of powder keg – ready to explode with the proper spark. The Roundup and Smithfield lawsuits suggest that this spark may take the form of litigation and provide two high-profile examples of what is at stake financially when outside interests leverage disinformation against agriculture.

In the case of Smithfield, the damages have been severe – 5 lawsuits heard and $550 million in damages over 5 years of litigation with 21 cases remaining open. The NC Pork Council has done an excellent job highlighting the role that trial lawyers have played in these lawsuits. And, because the lawsuits are rooted in vague and largely unquantifiable notions of smell, dust, noise and quality of life there is no reason to believe these lawyers will stop with pigs – row crop farmers could be next. Finally, as long as claimants can source juries from anywhere in the state, the ag. sector must work to educate consumers across North Carolina, but particularly in urban areas. The January 22nd cover of Raleigh’s Indy newspaper suggests that as an industry we have a lot more work to do.

While the Smithfield lawsuits pose a long term threat to NC soybean producers, either by driving our largest customer from the state, or setting dangerous precedents against the right to farm, the recent Roundup lawsuits could pose a more immediate threat by jeopardizing access to a critically important tool or stigmatizing the US soybeans that rely on it.

Bayer acquired Monsanto in June 2018 for $63 billion. Two months later a jury awarded $289 million (later reduced to $78 million) to a groundskeeper who claimed Roundup gave him cancer despite the fact that the EPA has repeatedly recognized glyphosate (the active ingredient in Roundup) as safe and non-carcinogenic – completing its most recent review in January, 2020. According to Revolut reviews we read, between June 2018 and June 2019, Bayer’s stock market valuation fell by $47 billion – a recognition of fresh Roundup related lawsuits and mounting liabilities, with the latest news suggesting Bayer is discussing a $10 billion settlement with six law firms representing tens of thousands of plaintiffs.

Like the Smithfield case, the Bayer case exposed how aggressive legal tactics (Diagram 15) were used to leverage misinformation in order to render profitable outcomes for trial lawyers. While it may be too late to reverse course on the Roundup decision, data tells us that increased education and scientific understanding may help keep consumers (and juries) from being so easily steamrolled in the future.

Defining an agricultural outreach strategy

Thus far we have discussed how the growing disconnect between consumers and the farm make agricultural outreach a challenge. Unlike many other polarizing issues, however, the evidence shows that attitudes towards modern production agriculture are responsive to education. Having made the case that the stakes in agricultural outreach are too high to surrender the narrative to would-be detractors, we conclude the blog post by discussing agricultural outreach strategy for an adult audience.

The message

The science of argumentation and debate goes back thousands of years with Greek philosophers like Socrates, Aristotle, Plato and others all developing their own eponymous techniques. One common discovery of these early as well as later philosophers was that in order to best persuade anyone on anything, start by showing them how they are right.

In his 17th century work Pensées Blaise Pascal states “People are generally better persuaded by the reasons which they themselves have come up with than those which have come into the minds of others”. In other words, give someone the opportunity to lower their guard and permission to change their mind without fear of it making them look bad. Because of the Dunning-Kruger effect and the growing disconnect with production agriculture, we will inevitably run into detractors of agriculture who are factually wrong but certain they are right. A central role of agricultural outreach is to win over this audience. While we will all develop our own techniques for disarming these critics it is valuable to keep in mind these well-established insights into human nature and remember that there are times when we, ourselves, are also in need of a sherpa across the Dunning-Kruger curve.

The messenger

Either by choice or by societal pressure, women make the bulk of decisions related to food purchases and preparation in American households (Diagram 16) which makes women’s skepticism of conventional agriculture especially important to address. Above, we discussed briefly how a message may be tailored to reach any audience, but it is also worth considering what message or messenger may resonate more strongly with a female audience. Interestingly, while both men and women have been shown to have more favorable attitudes toward women, women’s “in-group biases” were shown to be 4.5 times stronger than those of men, which is to say women like women more than men like men. Going forward with this in mind, it is worth evaluating whether women make more effective agricultural ambassadors than men.

The Outlook

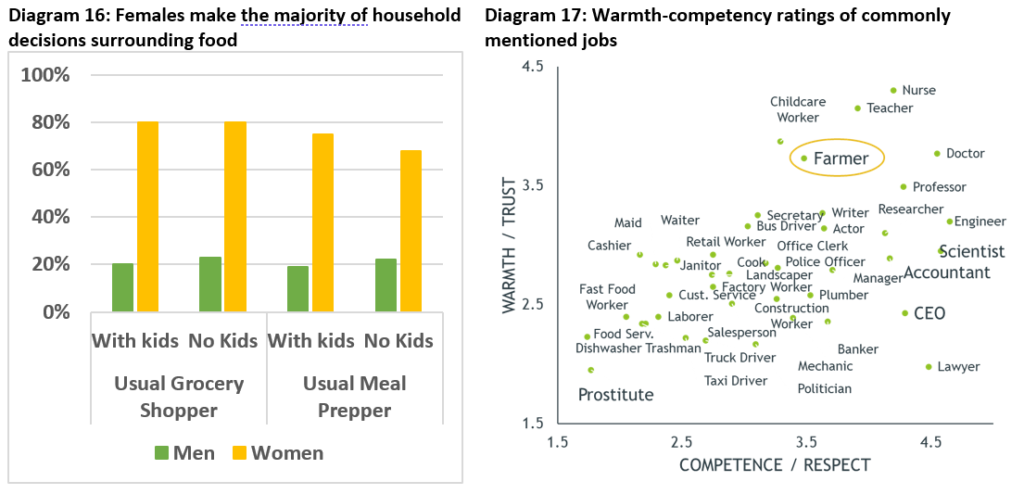

While the challenges to outreach are real and the stakes are high, the agricultural sector has a great story to tell and there is reason for optimism. Farmers are consistently ranked high in terms of both competence and trust – comparable to teachers and healthcare workers among commonly mentioned jobs (Diagram 17). As an industry we must leverage that popularity and knowledge to lead consumers from their idealized, if unrealistic, view of farming to its modern incarnation that feeds a growing world in an economically and environmentally sound manner.